The use of spectral data to predict soil organic matter in European

soils

Soil

organic matter

Soil organic

matter (SOM) is the fraction of the soil that consists of plant and animal

detritus (remains, waste products and other organic debris) at various stages

of decomposition (breakdown), cells and tissues of soil microbes, and

substances that soil microbes synthesize. It is estimated that concentration of

SOM in most of the productive agricultural soils ranges between 3 % and 6 %.

Even though it is only a small part of soil organic matter contributes to soil

productivity in numerous ways and the various components of organic matter

influence different properties of soil.

From the

chemical point of view SOM is composed mainly of just a few chemical elements

namely carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. These elements together make almost 92 % of

all SOM. However, organic matter also contains small amounts of other essential

elements, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, potassium, calcium and

magnesium which are encompassed in organic residues.\A0

Generally,

SOM is divided into living and dead components which can range from

very recent inputs, such as stubble, to largely decayed materials that are

thousands of years old. It is estimated that about 10 % of below-ground SOM,

such as roots, fauna and microorganisms, fall into the living category (see Fig. 1).

It is

normally considered that SOM is made up of different components which

vary widely in size, turnover time and composition in the soil. These

components can be grouped into four major types:

1. Dissolved

organic matter;

2.

Particulate organic matter;

3. Humus;

4. Resistant

organic matter.

Fig. 1.

Composition of soil organic matter.

The living organic matter

includes such parts as the microorganisms responsible for decomposition

(breakdown) of both plant residues and active soil organic matter or detritus. Organic compounds in vegetal detritus includes

carbohydrates which range in complexity from simple sugars to the complex

molecules of cellulose, fats that are composed of glycerides of fatty acids,

like butyric, stearic, and oleic, lignins that are complex

compounds, formed from the older parts of wood, and are resistant to

decomposition, proteins, and charcoal. Humus is the stable fraction of

the soil organic matter that is formed from decomposed plant and animal tissue

and is the final product of the decomposition processes. The first two types of

organic matter (dissolved organic matter, particulate

organic matter) contribute to soil fertility because the breakdown of

these fractions results in the release of plant nutrients such as nitrogen,

phosphorus, potassium, etc. The humus fraction has less influence on soil

fertility because it is the final product of decomposition. Therefore, humus is

also called the stable organic matter.

However, it still has much importance to soil fertility because it contributes

to soil structure, soil tilth, and cation exchange capacity. This is also the

fraction that darkens the soil\92s color.

There are many benefits of soil

organic matter in an agricultural soil. These

benefits can be grouped into three categories:

Physical

Benefits

●

Enhances aggregate stability, improving water infiltration and

soil aeration, reducing runoff.

●

Improves water holding capacity.

●

Reduces the stickiness of clay soils making them easier to till.

●

Reduces surface crusting, facilitating seedbed preparation.

Chemical

Benefits

●

Increases the soil\92s cation-exchange capacity or its ability to

hold onto and supply over time essential nutrients such as calcium, magnesium

and potassium.

●

Improves the ability of a soil to resist pH change (also known as

buffering capacity).

●

Accelerates decomposition of soil minerals over time, making the

nutrients in the minerals available for plant uptake.

Biological

Benefits

●

Provides food for the living organisms in the soil.

●

Enhances soil microbial biodiversity and activity which can help

in the suppression of diseases and pests.

●

Enhances pore space through the actions of soil microorganisms.

This helps by increasing infiltration and reducing runoff.

Evaluation of soil organic matter concentration

Due to the

forementioned benefits of soil organic matter it is regarded as one of the key

parameters (characteristics) of soil and is measured routinely to monitor the

soils health and condition. Due to the complexity of the composition of soil

organic matter it is difficult to directly evaluate its amount. This is why

most often the concentration of SOM in soil is determined first by determining

the total carbon content - soil organic carbon (SOC). Then SOM is evaluated

from the calculated value of SOC. The calculation between the concentrations of

SOC to SOM has historically formed to be a simple act of multiplication by a

constant ![]() \A0(van Bemmelen factor):

\A0(van Bemmelen factor):

![]()

The value of

the constant ![]() \A0is derived from the assumption that soil

organic matter is comprised of 58 % of carbon. However,

throughout the years the legitimacy of this value was put under question.

Several studies have shown that the conventional carbon-to-organic matter

conversion factor is too low for universal application and fails to account for

the significant variation in the carbon content of soil organic matter.

Therefore, there have been many suggestions on what value of the constant should

be used for soils regarding their composition (see Table 1).

\A0is derived from the assumption that soil

organic matter is comprised of 58 % of carbon. However,

throughout the years the legitimacy of this value was put under question.

Several studies have shown that the conventional carbon-to-organic matter

conversion factor is too low for universal application and fails to account for

the significant variation in the carbon content of soil organic matter.

Therefore, there have been many suggestions on what value of the constant should

be used for soils regarding their composition (see Table 1).

Table 1. The evaluated values of conversion

factor in different countries and soils (D. W. Pribly,

2010).

|

Country |

Soil description |

Factor value |

Reference |

||

|

Low |

Average |

High |

|||

|

Belgium |

Soils (rich in organic matter) |

1.44 |

2.05 |

3.10 |

De Leenheer et al. (1957) |

|

Denmark |

Forest |

1.55 |

2.63 |

15.4 |

Christensen and Malmros (1982) |

|

England |

Mineral; agricultural |

2.52 |

3.45 |

14.1 |

Warrington and Peake (1880) |

|

England |

Forest; Wetlands |

1.78 |

2.07 |

3.62 |

Howard (1964) |

|

Europe |

Forest; grass; peat |

1.97 |

2 |

2.5 |

Ponomareva and Plotnikova (1967) |

|

US |

Mineral |

1.63 |

1.92 |

2.14 |

Alexander and Byers (1932) |

|

Wales |

Peat |

1.86 |

1.88 |

1.95 |

Robinson et at. (1929) |

|

Wales |

Mineral and organic |

1.74 |

2.73 |

5.64 |

Ball (1964) |

|

Worldwide |

Mineral and organic |

1.35 |

1.74 |

2.44 |

Robinson (1927) |

|

Worldwide |

Surface soils |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

Broadbent (1953) |

Various

experimental and theoretical studies were performed in order to evaluate the

optimal value of the conversion factor and one of the most suggested value is ![]() \A0(Douglas W. Pribly, 2010).

\A0(Douglas W. Pribly, 2010).

The standard

practice for determining

organic carbon is performing chemical analysis of the

soil. This method involves a lot of procedural tasks and chemical reagents but

provides an accurate value of the SOC. However, the time and economic resources

needed for such analysis are not favorable because the evaluation of SOM cannot

be efficiently upscaled for larger fields or continuous monitoring. Such

drawbacks of the standard SOC analysis techniques led to the emergence of other

SOM evaluation techniques. One of them \96 hyperspectral or multispectral

spectroscopy, has gained a lot of traction in the past decade and is becoming

more and more applied for determination of all sorts of soil parameters

(citation).

Hyperspectral and multispectral imaging

Hyperspectral

imaging (HSI) spectroscopy is a modern and informative method belonging to the

larger group of spectroscopy and spectral photography methods. Hyperspectral

imaging technology is based on detection of the electromagnetic radiation

reflected (most often) from the analyzed object (sunlight is usually used as

the source of radiation) and collected in a vast range of spectral bands. The

reflected light is detected using passive type scanning or snapshot sensors.

Hyperspectral imaging spectroscopy is a remote sensing method which differs from other non-destructive remote spectroscopy methods

in that during the scanning or instantaneous capture

procedures a three-dimensional data array (so called hyperspectral cube) is

generated. Hyperspectral cube can essentially be described as a

three-dimensional data format where two dimensions (let\92s say x-axis and y-axis) describe the

spatial coordinates and the third dimension (z-axis) describe the spectral coordinates (wavelength). One

hyperspectral image can have tens or hundreds of spectral bands and each pixel

of the image presents the reflected and sensor-recorded electromagnetic

radiation intensity. Depending on the design and technical parameters,

hyperspectral sensors can record information starting with ultraviolet light

part of the spectrum (wavelength from around 200 nm) and ending in the

long-wave infrared light (wavelength up to 15 μm).

Hyperspectral imaging technology due to its informativeness and ease of

application is used in many different fields: medicine, food industry, material

property research, natural resource exploration, land on the farm, etc. Such

a wide range of applications is provided by the

physical nature of the method, which can be briefly described as the

fundamental interaction of the electromagnetic radiation and matter (in terms

of molecular structures). Because of this, hyperspectral imaging spectroscopy

can be applied to

study the spectral properties of light reflected by objects under study in

order to identify the molecular compounds, determine their chemical and

physical properties.

Close to

hyperspectral, but simpler, and at the same time more primitive and less

informative, technology is multispectral photography. In the latter, spectral

images are generated by collecting the radiation data in much wider (several

tens of nanometers and more) spectral bands. In contrast to hyperspectral

sensors, multispectral sensors do not cover the full spectral range of the

camera operation range. A fairly simple comparison of the hyperspectral and

multispectral imaging results is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig.

2. Comparison of the data collected using multispectral (left) and

hyperspectral (right) imaging methods.

In regard to the quality

of the hyperspectral images, three main resolution parameters which determine

the level of gathered information can be described. These are:

●

Spatial resolution;

●

Spectral resolution;

●

Temporal resolution.

Spatial

resolution is described as the smallest discernible detail in an image. It can

be regarded as the dimension of the smallest object in an image that can be

distinguished as an individual part. Spatial

resolution is directly related to the clarity of the image. However, it should

be mentioned that spatial resolution should

not be mixed up with the number of pixels in

an image. The spatial characteristics of a hyperspectral image depend on the

design of the imaging sensor in terms of its field of view and the altitude at

which the image is captured. If we consider that a finite patch of the ground

is captured by each detector in a remote imaging sensor then the spatial

resolution is inversely proportional to the patch size. Therefore, the smaller

the size of the patch, the higher details can be interpreted from the observed

scene.

Spectral

resolution is defined as the number of spectral bands in the whole range of

electromagnetic spectrum captured by the sensor. For example, the sensor might

collect the light in a large frequency range but still have a low spectral

resolution if the information is gathered from a small number of spectral

bands. On the contrary, if a sensor collects the data from a small frequency

range but captures a large number of spectral bands, high spectral resolution

is obtained. In such cases it is possible to distinguish between two similar elements

(having similar spectral features). Multispectral images, therefore, have a low

spectral resolution and using this method it is not possible to resolve finer

spectral signatures present in the analyzed area. HSI sensors acquire images in

numerous continuous and extremely narrow spectral bands in mid infrared, near

infrared and visible parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. This type of advanced imaging system shows tremendous potential for material

identification on the basis of their unique spectral signatures. Spectrum of a

single pixel in a hyperspectral image can give considerably more information

about the surface of the material than a normal image. It is worth mentioning

that even though multispectral imaging does not have as high spectral

resolution as hyperspectral imaging, oftentimes

it is much more practical to use. For example, in some cases it can be known

for certain in which specific parts of the electromagnetic spectrum largest variations or differences between the

spectral information of the analyzed objects are present. Therefore, collecting

the information in the whole spectral range does not provide any more useful

information and only burdens the analysis by adding redundant information.

Temporal

resolution is considered if routine measurements of hyperspectral or

multispectral remote sensing are made. In such cases depending on the type of information acquisition method

the temporal resolution can depend on the orbital characteristics of the

imaging sensor or the period of the experimental tests. Generally, the temporal

resolution can be defined as the time needed to revisit and obtain data from

the exact same location. Therefore, temporal resolution is considered high if

the period between two measurements of the exact same location is short and is

considered low if the said period is long. In general practice this parameter

is defined in days.

Collection of the spectral data

Remote sensing applications

provide unprecedented data streams for the retrieval and hence allow the

monitoring of SOC across the VNIR\96SWIR spectral range. The different sensors

used to collect the spectral data are generally mounted on either airborne or

spaceborne platforms. Also, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems have become

available to carry out the fully autonomous hyperspectral analysis. All

available remote sensing platforms can be differentiated in terms of their

spatial, spectral, and temporal resolution that consecutively specifies their

accuracy and the field of application. To put it in brief, different sensing

applications can be applied using three systems: satellite, airborne, and

unmanned aerial vehicle systems.

Satellite remotely sensed

imagery has a lot of potential to generate spatial maps of the upper soil

horizon. Satellite multispectral sensing was first used in quantitative SOC

characterization as soon as the first satellites were launched in the 1980s.

The hyperspectral data became increasingly popular several years later when the

Hyperion spaceborne system became operationally available. Nowadays, there are

few studies using satellite sensors for SOC estimation. Due to the increased

satellite data availability the SOC estimation and mapping based on spaceborne

data is starting to be increasingly developed. This was enabled by various

factors like distribution of the Landsat at no charge, free and open access

Sentinel-2 super spectral imagery data, as well as by the emergence of large

fleets of small satellites like Planet Cubesats. The

future prospects are also bright since a lot of hyperspectral imaging

satellites are planned to be put into orbit. The forthcoming projects are the

German Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program (EnMAP),

Italian PRecursore IperSpettrale

della Missione Applicativa (PRISMA), the U.S. NASA Hyperspectral Infrared

Imager (HyspIRI), the Japanese Hyperspectral Imager

Suite (HISUI), the Israeli Hyperspectral imager (SHALOM), and the China

Commercial

Remote-sensing Satellite

System (CCRSS).

Airborne hyperspectral

imaging has its benefits by offering the ability for the spatial assessment of

soil conditions with higher accuracy. Even though the imaging field is not as

large as with satellite data, the produced information can cover large areas

even from a single flight mission. The use of aircrafts can also provide the

data for segmentation of the investigated site in accordance to its soil

heterogeneity. Aircrafts have high capacity and can carry great payloads what

gives the ability for wide spectral range hyperspectral sensors to be mounted

on them and interchanged between flights. In addition to that, airborne mounted

sensors show more flexibility since it is possible to select the optimal flight

conditions, while having the added advantage of operating under a high-cloud

coverage.

Unmanned aerial vehicles

are popular since they can act as a low-cost observational platform for

environmental monitoring. UAVs can make use of the latest advances in sensor

science. In particular advancements in the size and spectral resolution of

state-of-the-art sensor systems. This combined with the reduced cost of both

the cameras and platforms are the main reasons why the use of UAVs has

exponentially increased for local investigation applications. UAVs show

characteristics of spaceborne and airborne platforms (by having a short revisit

time and high spatial resolution). Therefore, these systems represent a unique

opportunity to provide the resolution needed to cover various landscapes. Regardless

of these advantages, there are limits concerning the estimation of soil due to

the stability of the systems, the spectral range of the sensors, payload limits

and the limited flight duration of UAVs, and issues regarding image processing.

The comparison of the

advantages and disadvantages of the different data collection systems are

provided in Table 2.

Table 2. The main advantages and disadvantages of the remote sensing

platforms Adapted from (T. Angelopoulou, et\A0 al., 2019).

|

System |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Satellite |

Covers large areas. Provides information from inaccessible areas. Provides auxiliary data. Consistent temporal resolution. Short revisit time. Free data. |

Atmosphere absorption has a high impact. Low signal-to-noise ratio due to a short integration time. Mixed pixels contain more than bare soil surface. Need for geometric, atmospheric corrections. |

|

Airborne |

Provide information from inaccessible areas. High payload. High spatial resolution. |

Need for certain meteorological conditions. Legal constraints for the flights. High operational complexity. High cost. |

|

UAV |

Flight plans can be scheduled according to weather conditions. High spatial resolution. |

Limited payload Atmospheric, geometric corrections are needed. Legal constraints for the flight. |

Analysis of hyperspectral and multispectral images

If one wants to get the most of the

information from the hyperspectral or multispectral analysis, it is of much

importance to understand what kind of information is \93carried\94 in the collected data. All objects

present on the surface of Earth (all molecules for that matter) can absorb,

transmit and reflect electromagnetic radiation. Furthermore, the mentioned

types of interactions of the object and the electromagnetic radiation varies

depending on the type of molecules. Therefore, the collected spectra are unique

for objects of different composition. Since the electromagnetic radiation that

is radiated on the surface of the soil is reflected in distinct wavelengths the

resulting spectrum encodes data which is able to provide information to derive

qualitative and quantitative information of soil characteristics. VNIR\96SWIR

spectroscopy is based on characteristic vibrations of chemical bonds in

molecules. Particularly, in the visible region (400\96700 nm) the electronic

transitions generate wide absorption bands related to chromophores that affect

soil color, while in the NIR\96SWIR (700\962500 nm) weak overtones and combinations

of these vibrations occur due to stretching and bending of the N-H, O-H, and

C-H bonds. Hyperspectral and multispectral sensors allow measurement of all

types of electromagnetic energy within a specified range as it interacts with

materials. This creates a possibility to observe the distinct features and

changes on earth\92s surface. In normal hyperspectral and multispectral

experiments out of the mentioned three types of interactions (reflection,

absorption, transmission) reflectance due to the ease of its analysis is

determined. Reflectance is the measure of the amount of electromagnetic energy

bouncing back from a material\92s surface in regard to the amount that has fallen

onto the material in the first place. It is calculated as a ratio of reflected

electromagnetic radiation energy to the incident energy as a function of

wavelength:

![]()

Here, ![]() \A0\96 the intensity of the incident radiation, and

\A0\96 the intensity of the incident radiation, and

![]() \A0\96 the intensity of the reflected radiation.

Reflectance is 100 % if all the light energy striking the object is reflected

back to the imaging sensor. On the other hand, reflectance is 0 % if the entire

incident light is absorbed or transmitted by the object. Keeping in mind that

specific molecules interact with light in a unique way, in a specified range of

electromagnetic spectrum, the reflectance spectra of different materials on the

earth\92s surface such as soil (and its components), forest, water and minerals

will be different. The parts in which reflectance spectra are different are

regarded as spectral signatures or spectral markers. Remotely sensed images can

be classified using spectral markers, as each material present in has its own

unique spectral signature. The higher the spectral resolution of an imaging

sensor, the more information can be obtained in the collected spectra.

Hyperspectral sensors have higher spectral resolution than multispectral

sensors and thus the information gathered by HSI spectroscopy allows to

distinguish more subtle differences. Because of that, HSI is utilized by

geologists for mapping the land and water resources. It is also used to map

heavy metals and other hazardous wastes in historic and active mining areas.

The reflectance spectra of green vegetation, dry bare soil, and clean water are

compared graphically in Fig 3. It can be observed that the reflectance spectrum

for bare soil has fewer absorption bands (dips in the spectral contour) as

compared to that of green vegetation. This is resulting due to the factors

which affect the reflectance of soil (soil composition) vary in a narrow range

of electromagnetic spectrum. These factors include soil texture, presence of

minerals such as iron, surface roughness and moisture content in soil. Spectral

markers (absorption bands) of green vegetation are observed in the visible

range of the spectrum. This indicates the pigmentation in the tissues of the

plant of which chlorophyll is the primary photosynthetic pigment in green vegetation.

It is known that chlorophyll absorbs strongly in red (670 nm) and blue (450 nm)

regions which are called the chlorophyll absorption spectral bands. If a plant

is under stress the chlorophyll synthesis is reduced and the amount of

reflectance in the red (670 nm) region is shown to increase. The spectral

response of water has distinctive characteristics of absorption of light in the

near infrared region and beyond it. Common factors which affect the spectrum of

water are the suspended sediments and increased chlorophyll levels. In each

case the spectrum will change in accordance to the number of suspended

sediments or algae in water. The analysis of specific parts of the reflectance

spectra are the most sophisticated type of spectral data analysis which can

provide a detailed answer of the true nature of the spectral difference.

However, such requires a lot of expertise in the field of spectroscopy.\A0

\A0\96 the intensity of the reflected radiation.

Reflectance is 100 % if all the light energy striking the object is reflected

back to the imaging sensor. On the other hand, reflectance is 0 % if the entire

incident light is absorbed or transmitted by the object. Keeping in mind that

specific molecules interact with light in a unique way, in a specified range of

electromagnetic spectrum, the reflectance spectra of different materials on the

earth\92s surface such as soil (and its components), forest, water and minerals

will be different. The parts in which reflectance spectra are different are

regarded as spectral signatures or spectral markers. Remotely sensed images can

be classified using spectral markers, as each material present in has its own

unique spectral signature. The higher the spectral resolution of an imaging

sensor, the more information can be obtained in the collected spectra.

Hyperspectral sensors have higher spectral resolution than multispectral

sensors and thus the information gathered by HSI spectroscopy allows to

distinguish more subtle differences. Because of that, HSI is utilized by

geologists for mapping the land and water resources. It is also used to map

heavy metals and other hazardous wastes in historic and active mining areas.

The reflectance spectra of green vegetation, dry bare soil, and clean water are

compared graphically in Fig 3. It can be observed that the reflectance spectrum

for bare soil has fewer absorption bands (dips in the spectral contour) as

compared to that of green vegetation. This is resulting due to the factors

which affect the reflectance of soil (soil composition) vary in a narrow range

of electromagnetic spectrum. These factors include soil texture, presence of

minerals such as iron, surface roughness and moisture content in soil. Spectral

markers (absorption bands) of green vegetation are observed in the visible

range of the spectrum. This indicates the pigmentation in the tissues of the

plant of which chlorophyll is the primary photosynthetic pigment in green vegetation.

It is known that chlorophyll absorbs strongly in red (670 nm) and blue (450 nm)

regions which are called the chlorophyll absorption spectral bands. If a plant

is under stress the chlorophyll synthesis is reduced and the amount of

reflectance in the red (670 nm) region is shown to increase. The spectral

response of water has distinctive characteristics of absorption of light in the

near infrared region and beyond it. Common factors which affect the spectrum of

water are the suspended sediments and increased chlorophyll levels. In each

case the spectrum will change in accordance to the number of suspended

sediments or algae in water. The analysis of specific parts of the reflectance

spectra are the most sophisticated type of spectral data analysis which can

provide a detailed answer of the true nature of the spectral difference.

However, such requires a lot of expertise in the field of spectroscopy.\A0

Fig. 3. Reflectance spectra of

different types of earth\92s surfaces (M. J. Khan, et al., 2018).

Less sophisticated and

more approachable analysis of the reflectance spectra in order to determine the

earth\92s surface composition and distinguish between the different types of

objects, can be performed using the so-called vegetation indices. These indices

are parameters evaluated by combining the values of reflection spectra taken

from different spectral bands. The vegetation indices are derived

experimentally and most often represent a certain type of classification

problem. For example, one of the most popular vegetation indices is the

Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) which is calculated by the

following equation:

![]()

here the ![]() \A0\96 reflection value at 798 nm and

\A0\96 reflection value at 798 nm and ![]() \A0\96 reflection value at 670 nm. This index can

be used to identify the green vegetation. Therefore, it is used to distinguish

between plants and soil, also it can be used to evaluate the condition of the

vegetation (healthy, sick, etc.). There are a lot more indices to choose from

which should be done carefully when tackling a specific problem.

\A0\96 reflection value at 670 nm. This index can

be used to identify the green vegetation. Therefore, it is used to distinguish

between plants and soil, also it can be used to evaluate the condition of the

vegetation (healthy, sick, etc.). There are a lot more indices to choose from

which should be done carefully when tackling a specific problem.

One more possible

approach of the spectral data can be done using mathematical algorithms or

chemometrics. This type of analysis most often ignores the spectral information

and analyses the spectral data as a whole. The finding of the differences or

the correlation of certain spectral features are thus given as a task to the

mathematical algorithms. These can range from the fairly simple clustering or

principal components algorithms to the much more advanced machine learning or

neural network methods.

\A0

Analysis of soil organic matter from hyperspectral or multispectral images

It is possible to evaluate the amount of soil organic carbon (and thus soil organic

matter) from the hyperspectral or multispectral images of the soil. It can be

done using one of all of the previously

mentioned analysis methods. By analyzing the raw spectral data, wavelength

regions having highest importance for SOC estimation can be identified. Many

studies were dedicated to finding these

spectral regions. One of the first researches

which observed how organic matter influences

the reflectance spectra of soil showed that different spectral features of

different levels of organic matter oxidation can be observed (S. A. Bowers, et

al., 1965). Other

research showed that OH groups have strong absorption features at the regions

of 1400\961900 nm, mainly due to soil water content, hydroxyls and clay content

(E. Ben-Dor, et al., 1995). It was also observed that

the reflectance spectrum of soil at specific

wavelengths could be correlated with organic components like cellulose, lignin

or starch (E. Ben-Dor, et al., 1997). It was found

that the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum could also provide valuable

information for SOC estimation, considering that soil appears darker if SOC

content in the soil is higher (M. Ladoni, et al.,

2010). The spectral regions which are used most often in various studies are

highlighted in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Most prominent

spectral regions for SOC estimation from VIS-NIR reflection spectrum (T. Angelopoulou, et al., 2019).

One of the

key moments for accurate evaluation of SOC is the distinction between soil and

vegetation in the spectral data. Various vegetation indices could be of use for

this purpose. For example, one recent study on the possibilities of using

spectral images for soil analysis (Castaldi et al.,

2019) also performed the evaluation of SOC. The article focuses on issues of

accuracy and reliability, however, a couple of equations which allow the

calculation of the SOC from the spectral images by using indices is provided.

The described procedure is combined from several tasks. In order to create a

SOC map such procedures should be performed:

- NDVI

index is calculated from the reflection spectra. The NDVI is used to

identify the pixels which represent vegetation. All values

of the resulting NDVI layer which are higher than 0.35 are

removed. These values on the ground surface show a vegetation cover that is not

needed when assessing soil properties.

- Green

vegetation indices (GVI1 and GVI2) are calculated. These indices can be

evaluated by the following relations:

![]()

![]()

Pixels which have negative values of such indices

are also removed from the image. Such procedure improves the discrimination

between the soil and vegetation.

- Normalized

Burn Ratio 2 (NBR2) is calculated. Normally this index is used to evaluate

the burnt-out land, however, in this case it was used to distinguish

between the soil with high levels of moisture. The NBR2 is calculated as

follows:

![]()

The pixels representing heavily irrigated soil ![]() \A0are removed and only dry soil is being

analyzed. If the analysis does not require a high level of precision,

the NBR2 threshold can be increased to 0.075 or even 0.1.

\A0are removed and only dry soil is being

analyzed. If the analysis does not require a high level of precision,

the NBR2 threshold can be increased to 0.075 or even 0.1.

- After

the spectral images are cleaned (the pixels which are not suitable for

analysis are discarded) the SOC index is calculated in the remaining

images. The SOC is evaluated through the red edge carbon index (RECI).

This index is evaluated by the following relation:

![]()

Using the calculated RECI values the amount of

SOC (expressed in g/kg) is calculated in the following manner:

![]()

- Using

the calculated values, a map of soil organic carbon is generated.

For the

accuracy analysis of the values obtained in the map are

correlated with data from laboratory tests on soil samples, taken from the same geographical coordinates. These points were used to verify accuracy and

errors of the method used. Finally, the organic carbon content is converted

into SOM by the already mentioned relation:

![]()

\A0

The SOM

content can be evaluated from the spectroscopic data not only by using

vegetation indices. In fact, on most occasions the concentration of SOM in the

topsoil is evaluated by creating mathematical models. Such models take into

account both the spectroscopic data and the available data on the real SOM

concentration which was evaluated using standard chemical analysis methods. The

mathematical models are useful because they can automatically find the

correlation between the spectral features and the true values of SOM.\A0 However, correlating the spectral features

with the properties of the soil requires the use of multivariate statistical

methods also known as chemometrics. The most common approach for such analysis

is the use of partial least squares regression (PLSR) method which describes

linear relationships between the variables. Yet it has been observed that

relationships are not always linear (X. Peng, et al., 2014). Because of that,

machine learning algorithms are increasingly used for the evaluation of

correlation processes.

The true values of SOC

can be estimated during field experiments or can be extracted from the

available databases. For example, on such a database LUCAS database is profoundly used in many publications.

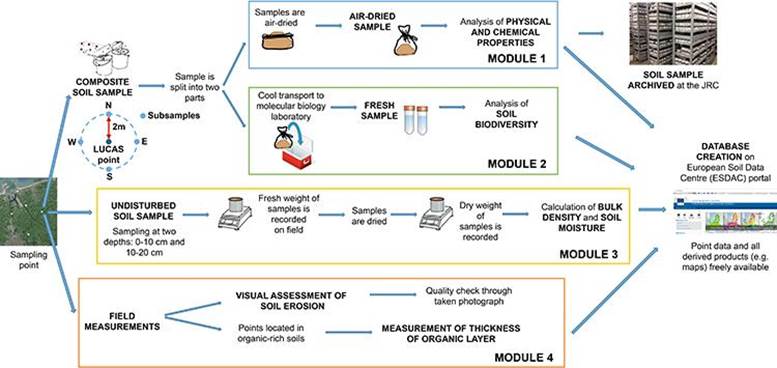

LUCAS database is composed by collecting the

soil samples all across Europe and evaluating different parameters. The whole

procedure of the creation of the LUCAS

database is presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. LUCAS Soil

workflow from sampling to database generation (A. Orgiazzi,

et al., 2018).

The attempt to evaluate

the SOC in European soil using

the LUCAS database and NIR spectroscopy was published

by Antoine Stevens, et al., 2013. In this study the accuracy to predict SOC

content of different algorithms was tested to evaluate the potential of using

the LUCAS soil database and to cover soil heterogeneity. Several performance

parameters were analyzed and the best spectroscopic models having the highest

parameter scores were chosen. These were then tested again by using a separate

test set. It was observed that the accuracy of the predictions of SOC highly

depended on soil classes (cropland, grassland, woodland mineral, and organic)

and the use of auxiliary predictors (sand and clay). The results of the tests \96

performance parameter values, are shown in Table

3.

Table 3. Performance of the best spectroscopic

models as measured against the test set (Antoine Stevens, et al., 2013).

|

Subset |

Treatmenta |

MVCb |

Predictorc |

SDd |

RMSEPe |

Biasf |

SEP-bg |

RPDh |

R2 |

Ni |

|

Cropland |

SG1 |

svm |

spc |

8.6 |

4.9 |

0.2 |

4.9 |

1.74 |

0.67 |

2828 |

|

Cropland |

SG1+SNV |

svm |

rfe+clay |

8.6 |

4.0 |

0.1 |

4.0 |

2.17 |

0.79 |

2828 |

|

Grassland |

SG1 |

svm |

spc |

17.4 |

9.3 |

-0.9 |

9.3 |

1.86 |

0.71 |

1383 |

|

Grassland |

SG0 |

cubist |

rfe+sand |

17.4 |

6.4 |

0.1 |

6.4 |

2.7 |

0.87 |

1383 |

|

Woodland |

SG1 |

svm |

spc |

29.8 |

15.0 |

0.8 |

15.0 |

1.99 |

0.75 |

1564 |

|

Woodland |

SG0 |

cubist |

rfe+sand |

29.8 |

10.3 |

1.1 |

10.3 |

2.88 |

0.89 |

1564 |

|

Mineral |

SG1 |

svm |

spc |

19.1 |

8.9 |

0.2 |

8.9 |

2.13 |

0.78 |

6053 |

|

Mineral |

SG1 |

svm |

rfe+sand |

19.1 |

7.3 |

0.1 |

7.3 |

2.62 |

0.86 |

6053 |

|

Organic |

SG1+SNV |

cubist |

spc |

100.8 |

50.6 |

-10.9 |

49.5 |

1.99 |

0.76 |

368 |

aSpectral

transformation (SG0 = Savitzky-Golay smoothing; SG1 =

Savitzky-Golay first derivative; SNV = standard

normal variate);

bMultivariate

Calibration Model (svm = support vector machine

regression; cubist = Cubist);

cPredictor

used in the models (spc = spectral matrix; rfe = spectral matrix with bands selected by recursive

feature elimination);

dStandard

Deviation of the observations (g\B7kg-1);

eRoot Mean

Square Error of Prediction (g\B7kg-1);

fBias (g\B7kg-1);

gStandard

Error of Prediction (g\B7kg-1);

hRatio of

Performance to Deviation;

iNumber of

validation samples.

As the

authors of the study state all the models have shown limited accuracy in

predicting the values of SOC. This suggests that accurate SOC predictions based on

large scale spectral libraries can be hard to achieve. Prediction errors were

found to be related to SOC variation, SOC distribution (skewness) and variation

in other soil properties such as sand and clay content. The authors state that

VIS-NIR spectral data alone may not be able to contain enough information to

get accurate predictions of soil properties at large scales. Therefore, other

strategies that can address this issue, such as the use of additional

predictors in the modeling should be taken. However, other studies have gotten

better results. For example, algorithm of partial least squares regression

(PLSR) was applied together with the LUCAS database and remote Airborne Prism

Experiment (APEX) spectral data in order to create a model for SOC estimation

in the croplands of Luxembourg and Belgium (Fabio Castaldi,

et al., 2018). In this study a so-called bottom-up analysis approach was taken.

According to the authors,

such an approach avoids the main errors which arise because large spectral libraries are built

collating local libraries that were collected under differing conditions and

using different protocols and instruments. This approach predicts the SOC

values at sampling points based on the LUCAS spectral library. Then these

values were linked to the airborne spectra building a PLSR model. Finally, the

PLSR model was applied to all bare soil pixels of the airborne image producing

SOC maps with the same spatial resolution as the airborne data. Thus, this

approach allows laboratory analysis of the target variable to be avoided. The

accuracy of the proposed method was compared with the traditional approach -

the calibration of a multivariate model which links remote spectra and the

quantity of the SOC measured in the laboratory. The flowchart of the proposed

analysis method is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The bottom-up

approach proposed by Fabio Castaldi et al., 2018.

The main difference

between the traditional and bottom-up approaches is that the latter does not

require analytical laboratory measurements. Instead, different soil variables

are estimated exploiting laboratory spectral data. The bottom-up approach

consists of two main steps:

- The

estimation of a soil variable at sampling points exploiting the LUCAS

spectral library and its ancillary data.

- The

mapping of the soil variables using remote-sensing data.

Artificial neural

networks were employed for the creation of the mathematical models for SOC

evaluation. NDVI was calculated in order to distinguish between the

hyperspectral imaging pixels representing vegetation and soil. The results of

this research have shown that the proposed bottom-up approach can provide the

results of SOC analysis in comparison to the standard approach involving the testing of the soil samples in the laboratory and correlating the results with the

data from the remote hyperspectral imaging.

A rather

complex and large study was performed in order to analyze the differences in

the spectral data provided by hyperspectral and multispectral imaging

satellites and to estimate the best approach for SOC evaluation

(D. \8Ei\9Eala, et al., 2019). The study was conducted in

the Chernozem region of Czechia. Field sampling and predictive modeling of the

spectral data was performed. The spectral data was collected from multispectral

Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, and PlanetScope satellites,

and multispectral Parrot Sequoia UAV. Aerial hyperspectral CASI 1500 and SASI

600 data was used as a reference. The data processing steps were as follows:

- Pixels

in individual data sources were filtered based on NDVI value. The

threshold was set to 0.25.

- The

filtered dataset was partitioned into a training set and a test set.

- A

mathematical model was trained using the training set. Several models were

tested and the final model was selected based on the smallest value of

root mean square error of cross-validation.

- The

accuracy of prediction was evaluated by determining the measure of

accuracy computed based on a comparison of observed and predicted values of

the validation set.

- Finally,

the best model was applied to the entire dataset of image spectral data.

The results

of the study have shown that very similar prediction accuracy for all

spaceborne sensors with only minor prediction variance can be obtained. The

results of the SOC mapping with the data from different imaging systems are

presented in Fig. 7.\A0\A0\A0\A0\A0\A0\A0\A0

Fig. 7. SOC maps

calculated using different remote sensing platforms (D. \8Ei\9Eala,

et al., 2019).

Several other studies

have tested the efficiency of the mathematical algorithms for soil analysis and

organic carbon concentration evaluation. A study done in Greece (P. Tziachris, et al., 2019), have compared several machine

learning algorithms and found that the result of the SOC evaluation is

dependent on the algorithm choice. It was determined that algorithms such as

Random Forest or Gradient Boosting show better accuracy than other methods like

Ordinary Kriging. A review on the different algorithms used for determination

of SOC content (S. Lamichhane, et al., 2019) has also

evaluated that machine learning algorithms provide more accurate results. This

study has also looked into the environmental covariates which are most

important for one of the machine learning algorithms (Random Forest).

Covariates representing organism activities were the most frequent among the

covariates, followed by the variables representing climate and topography.

Climate was reported to be influential in determining the variation in SOC

level at regional scales, followed by parent materials, topography and land

use. However, for mapping at a resolution that represents smaller areas such as

a farm- or plot-scale, land use and vegetation indices were stated to be more

influential in predicting SOC. Similar conclusions were drawn in another

study written by T. Angelopoulou, et al., 2020. The

authors find that the results of spectral SOC estimations are promising but

more research needs to be done in terms of selecting the spectral range,

preprocessing methods, and the calibration techniques. Also, as already

mentioned a specific importance should be kept on covariates such as soil

moisture, soil roughness, vegetation cover, and others that affect SOC spectral

response. Authors stated that various inconsistencies among studies should be

solved. Therefore, when publishing results more information should be included

about the experimental design, the criteria used for the selection of the

chemometric approach, and the pre- and post- processing procedures in order to

facilitate comparisons of results among studies.

A lot of effort is being

put in order to create the best tool for SOM evaluation from the spectroscopic

data. However, there is no census on what approach is the best as we can see

from the various publications and performed studies. Still a lot can be learned

to take the best approach possible at this time. What has to be taken into

account first is that spectral regions which can be used to quantify soil

organic carbon (SOC) are located mainly in broader bands in the visible region

of the spectrum and in the narrower bands of the SWIR spectrum (between 1600

and 1900 nm and around 2100 and 2300 nm). Because of that, the spectral

resolution of the sensors significantly influences the quality of SOC

predictions. Because of that it is necessary to use data with appropriate

spectral resolution taken across the VNIR-SWIR spectrum for accurate SOC

estimates. Second, a

well thought out method for processing the data

should be used. Usually, different thresholds of vegetation indices are used

for identifying and removing unwanted pixels in the image. Mainly NDVI for

green vegetation, NBR2, or MID-infrared for non-photosynthetic vegetation or

combined indexes, such as Bare soil index (BSI) or PV are used. Also,

statistical parameters \97 mean, median, or minimum or other methods used that

improve the image values are used. These for example, can be application of PCA

components, calculation of standard deviation or using low-pass filter.

Furthermore, it is necessary to develop new algorithms, not only for

identifying bare soils, but also for removing the influence of moisture,

surface roughness, or vegetation residues. Clouds and unwanted shades also affect the input data and should also be taken into account.

Lastly, the lack of comparability between different studies is a big issue.

Model evaluation and accuracy is investigated using different methods. Thus,

different studies are deprived of certain information which is essential for

the comparison between the results. What is more, different laboratories used

different protocols for soil sampling and measurements together with different

instrumentation. These factor in and hinder the reliability of the results. To

tackle this challenge a unified soil spectral library (SSL) potentially could

be a strong boost towards a more accurate prediction of SOM.